Hear rate monitors revealed higher stress levels than visible activity indicated.

Wildlife researchers have long struggled with removing the human element whenever possible, so as to monitor patterns like mating and migration without getting in the way. Hidden cameras help, but can only provide so much data. In recent years, camera-mounted drones have been considered for research, and the short-term data looked promising; in particular, anecdotal evidence suggested animals weren’t changing their activity much with drones flying overhead.

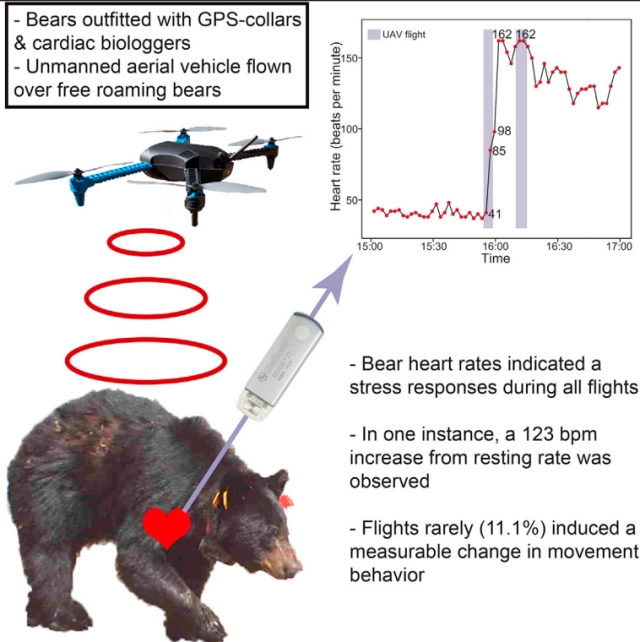

A research team at the University of Minnesota wondered if anything unseen might be happening during drone studies. So they put biologger collars on four adult bears and two cubs, then flew drones an average of 21 meters above their heads (and an average of 215 meters absolute distance) for five-minute spans. The results, published in Current Biology on Thursday, included a noticeable heart rate spike for all flown-over bears while the crafts were overhead.

In those five-minute windows, one bear’s heart rate climbed all the way from 41 beats per minute to 162, while the rest of the bears saw beats-per-minute jumps as low as 30 and as high as 80. Still, each bear had the spike in common, along with a resulting drop to a normal heartrate shortly afterward. This came despite a seeming lack of visible response, with the exception of one bear that appeared to react. The bears in the study included two mama bears and their respective cubs; a lone male bear; and a female bear on the verge of hibernation.

The study noted that the bears’ relatively quick heart rate recovery may be influenced by living in close proximity to human activity like farming and automobiles, but added that drones have the potential to “induce higher levels of stress” than higher-flying planes. After referring to a similar February study about drones’ impact on bird populations—which didn’t measure heart rate or other invisible stress indicators—the University of Minnesota researchers implored the scientific community to “answer important questions” before expanding research use of drones, “especially with regard to endangered species or areas of refuge.”

A 3DRobotics Iris drone, mounted with a GoPro HERO3+ camera, was used in each test; that drone has since been replaced with an Iris+ model, but even that model’s noise has been described to be “as loud as one thousand bees and a hummingbird.”

Party pooper

Some people certainly didn’t need to read such a story to recognize the ecologically disruptive ecological of unmanned drone aircraft. In at least one case, that’s the whole point.

Ottawa photographer Steve Wambolt started using a drone two years ago to take aerial shots of the city, but after being encouraged by city councilors, he modified his craft to create the “Goosebuster.” As The Wall Street Journal reported on Thursday, that six-rotor craft, armed with speakers that play the sounds of predatory birds, has been used ever since to shoo Canadian geese, and their pounds of poop, off the Petrie Island beach near his home.

He has since submitted a proposal to the Ottawa city council to expand his vigilante operation to scare the geese away from all city parks. According to the WSJ report, however, he has received opposition from the very councilor who asked for goose relief in the first place. Wambolt’s current campaign doesn’t appear to run afoul (yes, pun intended) of Ottawan drone rules, which currently require a permit for devices over 35kg and prohibit operating such devices near airports or higher than 90 meters in the air.

http://arstechnica.com/science/2015/08/drones-used-to-monitor-bears-send-their-heart-rates-through-the-roof/

Related:

http://www.iconaerialmedia.com/2015/08/14/drone-flights-overhead-cause-stress-for-black-bears-study-says/