U.S. lawmakers and the military worry about small consumer drones running afoul of planes and emergency crews. But there may be no simple fix.

By Patrick Tucker, Defense One

Senator Chuck Schumer speaks at New York University, August 11, 2015.(Andrew Burton/Getty Images)

August 25, 2015 Small consumer drones have become the plague that Moses missed. So far this year, 650 drones have been spotted by airline pilots. That’s on pace to quadruple last year’s total, which is troubling because if a pilot can see your drone in the air, it’s close enough to worry about. In July, a wildfire in California consumed 20 vehicles on a highway north of Los Angeles when consumer drones interfered with firefighters for the fifth time that month. And testing jet engines against consumer drones has proved to be a challenge.

To answer this growing problem, Sen. Chuck Schumer last week proposed an amendment that would require consumer drone manufacturers to build software-controlled no-go zones—so-called geofences—into their aircraft. The idea is to let software keep them away from airliners, emergency crews, and the like. “This technology works and will effectively ‘fence off’ drones from sensitive areas like airports,” Schumer said in a press release. Two recent hacker demonstrations show that’s somewhat wishful thinking.

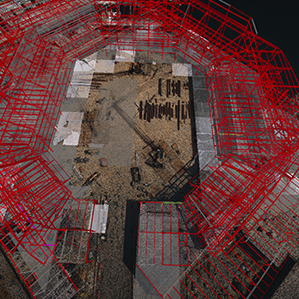

What is a geofence? It’s manufacturer-created software that prevents a drone from flying within certain GPS coordinates. Some drones already come with it; after an intoxicated General Services Administration employee crashed a friend’s DJI Phantom on the White House lawn in January, DJI issued a mandatory upgrade to its software: a geofence that prevents the popular toys from flying within 25 kilometers of the White House and other sensitive sites.

Schumer’s bill proceeds from the notion that such measures can keep drones out of trouble. But while geofences may help keep the average hobbyist away from the White House, hackers have already shown they can rip holes in them.

Earlier this month, researchers at the DEF CON hacker conference in Las Vegas, Nevada, demonstrated that the Phantom’s geofencing was easily manipulated in a variety of ways. Cybersecurity researcher Michael Robinson showed that the DJI Phantom III’s geofence draws upon a database that contained some 10,914 entries as of July 24. Each entry contains a country, city, a timestamp, and, more importantly, the latitude and the longitude of the no-fly zones, according to Robinson’s research.

“I very easily downloaded the database and started just changing entries, which I found very interesting,” he said.

Earlier this month, researchers at the DEF CON hacker conference in Las Vegas, Nevada, demonstrated that the Phantom’s geofencing was easily manipulated in a variety of ways. Cybersecurity researcher Michael Robinson showed that the DJI Phantom III’s geofence draws upon a database that contained some 10,914 entries as of July 24. Each entry contains a country, city, a time stamp, and, more importantly, the latitude and the longitude of the no-fly zones, according to Robinson’s research.

“I very easily downloaded the database and started just changing entries, which I found very interesting,” he said.

By tweaking the data, Robinson was able to make his Phantom ignore the manufacturer-set no-fly zones.

He said he also used a garage-made GPS spoofer to disrupt the geofence. He reported that the spoofer broke the drone’s return-home feature and compromised the video feed, which he described as suddenly “squirrely.”

Two other researchers, Lin Huang and Qing Yang, with the Internet security company Qihoo 360 out of China, also reported being able to disrupt a Phantom’s geofence by spoofing the drone’s GPS remotely, via software-defined radio. This is far more troubling because they didn’t need to have physical access to the machine, just be within range. But such results are harder to verify by independent American researchers because GPS spoofing is very, very illegal.

Perhaps more damning, the hackers demonstrated these tricks on products that the makers had actually undertaken some effort to secure. Phantoms use secure radio and GPS for guidance rather than the less secure WiFi or Telnet.

Defense One reached out to DJI Phantom for comment and has not heard back.

What does Robinson think of legislative efforts like Schumer’s? “With respect to policymakers, I would like to see policymakers get informed,” he said.

If the government can’t ward off drones using manufacturer-based geofences, what then? Don’t look to traditional military-grade air-defense systems, which are built to spot far larger and faster intruders. On April 15, a 61-year-old man named Doug Hughes took off from Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in a homemade gyrocopter and flew through three no-fly zones to the steps of the U.S. Capitol. “Identifying low-altitude and slow-speed aerial vehicles from other objects is a technical and operational challenge,” Navy Adm. William Gortney, commander of U.S. Northern Command and North American Aerospace Defense Command, or NORAD, later told the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform.

Still, the Federal Aviation Administration, the Homeland Security Department, and the military are giving it their best shot. On Sunday, NORAD staged an exercise near Washington, D.C., to test its ability to detect and intercept drones.

Last year, the military held the 10th edition of its Black Dart exercise, which focuses specifically on anti-drone defense. In recent Black Dart games, the military has focused more attention on so-called Group 1 drones: consumer quadrcopters and others under 20 pounds, like the one that crashed on the White House lawn, or the one that landed on the roof of the Japanese prime minister’s residence carrying a small amount of radioactive material back in April.

How do you differentiate between a 10-year-old kid who just doesn’t know any better and is flying something from a hobby shop and somebody who’s flying that identical something from a hobby shop but has nefarious intent?” said Air Force Maj. Scott Gregg. “You can’t tell that with a radar or an infrared sensor.”

Even if it’s possible to detect small drones like the DJI Phantom or the popular (and very hackable) Parrot BeBop as they move into sensitive areas, a bigger problem is taking them down in a way that doesn’t interfere with GPS or other electronic-signaling.

The defense industry wants in to the growing market of detecting and downing those diabolical drones. Scientific Research Corporation, or SRC, is marketing a set of systems they call “Counter UAS Technology.” Aimed at consumer-sized unmanned aerial vehicles, it uses radar and electromagnetic frequencies to down drones around a protected facility. “You’re going to be looking at acoustic sensors for very close. You’re going to be looking for electromagnetic warfare capabilities,” said Tom Wilson, SRC’s vice president of product accounts, who declined to get more specific about the system’s workings.

A company called Drone Shield also sells several acoustic sensors meant to detect drones near airports. But detecting and signal-jamming are very different, and the later presents serious legal hurdles. Drone Shield will sell you “a legal, safe, and reliable” drone net gun.

In the end, the best defense against small drones may lie somewhere between relying on manufacturer software updates (ineffective) and shooting them down (dangerous and uncouth). SRC’s Wilson said, “Our system is designed to operate without interfering with nonthreat systems.”

Failing that: Net gun, anyone?

http://cdn.defenseone.com/defenseone/interstitial.html?v=2.1.1&rf=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.defenseone.com%2Ftechnology%2F2015%2F08%2Fchuck-schumer-no-fly-zone-drones%2F119389%2F%3Foref%3Dd-river